Living with Black Bears Project – Expanding Eastward

–Contributed by Courtney Hallacher, DWR Statewide Wildlife Education Coordinator

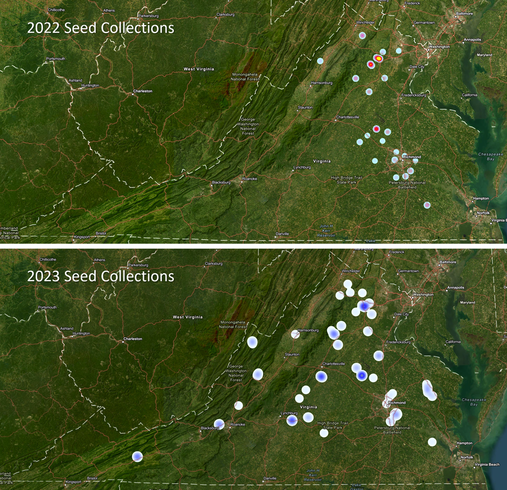

DWR is looking for additional VMN chapters to join the Living with Black Bears (LWBB) outreach and education project. As black bears have become more common across Virginia, DWR has teamed up with and trained VMN volunteers to provide important bear education within their communities in hopes of alleviating negative interactions and human-bear conflicts. Since the program’s inception in the summer of 2022, 12 chapters have joined the program: Riverine, Pocahontas, Fairfax, Roanoke, Central Blue Ridge, Rivanna, Headwaters, Alleghany Highlands, Southwestern Piedmont, Shenandoah, and Old Rag. Volunteers across these chapters combined have given 32 sit-down black bear presentations, staffed 37 black bear educational tables, and made 32,599 direct educational contacts, far more than DWR staff could do alone. We are incredibly grateful to our VMN black bear education teams!

If your chapter is looking for an outreach project, especially if you are in the eastern part of our state, consider the LWBB! Contact DWR Statewide Wildlife Education Coordinator, Courtney Hallacher, at courtney.hallacher@dwr.virginia.gov for more information and to join!

The project is making a difference! For sit-down presentations, volunteers distribute pre- and post-surveys. The evaluation results show educational impacts such as:

- Attendees indicate that they have higher knowledge of black bears after the presentation: 62% say they know a “little bit” about black bears before the presentation, while after the presentation 95% said they rate their knowledge as “a fair amount” (44%) or “a lot.” (50%).

- Before the presentation, 34% of people state that they take down their bird feeders when bears are active, after the presentation 75% of this same audience say they will now be taking down their bird feeders when bears are active.

- We also see a change in dog leashing, 30% prior to and 43% after the presentation. Dog leashing is of particular importance for human safety in the outdoors since a lot of physical contact with black bears is due to bear-dog-human interactions.

- From our survey it seems like people already secure their trash/camping food and are careful about preventing animals from accessing pet food so we see little difference between the before and after numbers, although the numbers do go up by an attendee or two.

We also receive anecdotal reports of project impacts. For example, a few days after attending a volunteer’s LWBB presentation, an attendee saw on her neighborhood email list that a black bear tore down a neighbor’s bird feeder. The individual took what she learned from the presentation and wrote a response back to all her neighbors and included the video recording of the presentation. Her response included removing bird feeders, potentially permanently until winter, along with removing other attractants. She described how bears will come back to look for that easy meal again and again until they realize it is not coming back out and then they will move on. The neighbor read the email and actually removed the feeder. They also set up a trail cam pointed at the place the feeder was located and a couple days later that bear actually showed back up looking for the feeder but it wasn’t there!

In another example, a volunteer wrote, “Everyone we talk to seems extremely interested and eager to hear about black bears since there are so many sightings. People want to learn more so they can understand why they’re seeing them, what to do/not do, and they’re curious why there are so many more bears than in the past. We get a huge variety of questions and lots of them. This project is SO worthwhile!!”

Living with Black Bears Project – Expanding Eastward Read Post »