Three Volunteers Tell Their Stories

Ivan Hiett has volunteered many hours at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, and he recently reached the milestone of 250 hours of service as a VMN volunteer.

Ivan Hiett has volunteered many hours at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, and he recently reached the milestone of 250 hours of service as a VMN volunteer.

Ivan Hiett, Certified Virginia Master Naturalist Volunteer in the Southwestern Piedmont Chapter:

Upon entering basic training orientation on the first day, I first thought maybe I was in the wrong classroom. I hadn’t expected that I’d be the only person of color in the group, but there I was deciding whether I should enter or not. After confirming this was indeed the Master Naturalist orientation class I decided to stay. After all I’d been in similar situations during my career and was successful. No one seem to mind or care about my race, well at least no one showed it. We had one thing in common in that we cared about protecting and conserving our natural resources. We all were supportive of each other and began to bond. I was impressed by the diverse backgrounds of participants of the class members. Each member shared valuable experiences and knowledge in a variety of topics.

Being the only person of color in training, I’d hoped to meet other minorities at chapter meetings but that didn’t happen. I accepted the fact that I’d be the one to break the ice. Being the only minority at meetings, group outings, and volunteer events was somewhat challenging, but I wouldn’t let that deter me. Everyone was very friendly and made me feel welcome although occasionally I felt some cohorts were not used to being around persons of color and may have been somewhat uncomfortable. But everyone was professional. I often wondered why other minorities hadn’t joined the group since we too are concerned about protecting our environment and natural resources. I concluded that most are probably intimidated at the prospect of being a minority in an organization of mostly Whites. As for me, college, and military travels prepared me to be an adventurer.

Volunteer service projects have been most challenging for me. While many of my volunteer hours were spent at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, I’ve also participated in group outings and other volunteer service projects. Not being a native of the Piedmont area, I wasn’t totally familiar with the culture or the resources of the area. Moving here I spent most of my time working and during vacations usually I traveled. I regret that I hadn’t taken time to get to experience the local area but becoming a VMN member gave me the opportunity to explore. Volunteer projects would have to be chosen carefully. Some potentially interesting projects was passed if I wasn’t comfortable with some aspects of the area. Understand some projects that are in remote rural areas may not be good for a person of color to visit. Visiting an area adorned with rebel flags and Trump signs probably wouldn’t be a good idea. This may sound petty or trivial to some but can be unsettling to minorities. Expect the unexpected. Fortunately, I have not experienced any issues or problems on any field trips or service projects that I’ve attended.

After being a member of my chapter for about a year, I was asked to assume the role of secretary. I was hesitant at first, but after some persuasion I accepted the position and was approved unanimously by members. A year later I was voted President of our chapter. I didn’t want to be observed as the token minority representative. However, being a board member gave me the opportunity to have a voice in chapter activities. Besides maybe I could pave the way for other minorities. I think to attract more minorities to the organization, we may need to focus more on projects that affect minority interests, their neighborhoods and recreation areas.

In conclusion I’d say my experience with VMN has been positive and rewarding. Once people of different cultures and backgrounds unite for a common cause, great things can happen. We must set aside our differences and focus on those things that matter to us. I’ll always remember the first day of basic training and thinking “I’m in the wrong place, this group is not for me”. We must put aside our negative preconceived notions and ideas toward the realization that we must work together to make our home (earth) a better place to live and preserve it for future generations.

“I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel”

~ Maya Angelou

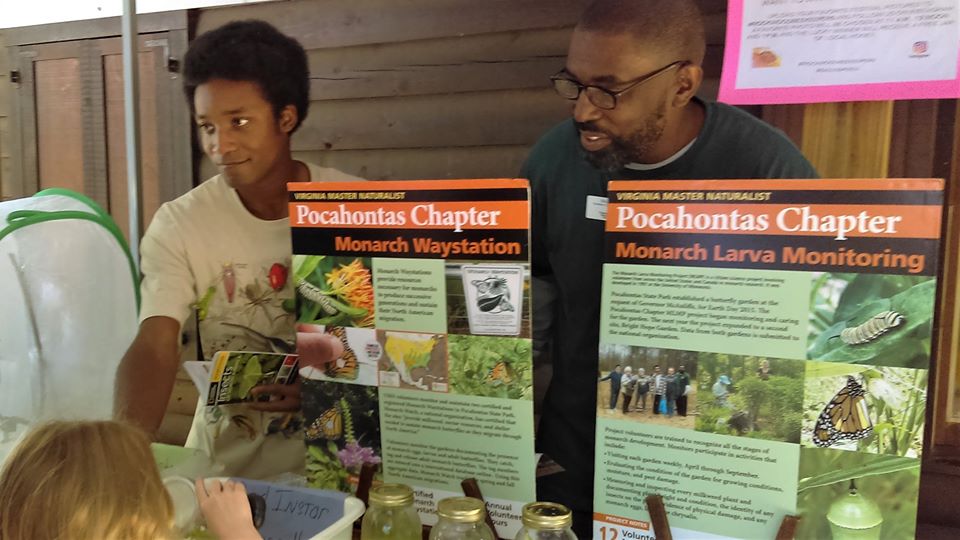

Joshquinn Andrews (left) and fellow VMN volunteer Eric Gray (right) share their enthusiasm for monarchs with the public. Photo by Mary Camp, VMN-Pocahontas Chapter.

Joshquinn Andrews (left) and fellow VMN volunteer Eric Gray (right) share their enthusiasm for monarchs with the public. Photo by Mary Camp, VMN-Pocahontas Chapter.

My name is Joshquinn Andrews and I am a Virginia Master Naturalist of the Pocahontas Chapter. I have been a member for six years.

Currently I primarily help with projects known as the Monarch Larva Monitoring Project and Monarch Watch. The former involves collecting data on the larva of the monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) and their host plants known as the milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) while the latter deals with tracking and researching the autumn migration of the monarch butterflies through tagging. Before joining this project, I had only seen butterflies and the stages of the monarchs through pictures. With my participation, I had the chance to see both the larva and pup

a stages of the monarchs for the first time. In fact, participating in the Monarch Larva Monitoring Project has also led me to see milkweed for the first time and the organisms that rely on the plant as a source of food. Some examples include the larva of the milkweed tussock moths (Euchaetes egle) and large milkweed bugs (Oncopeltus fasciatus).

Another experience I enjoy is participating in what is known as a Bio Blitz, in which we search Pocahontas State Park for different species of butterflies and keep tally of the number of species we spot. Through this experience I have explored new locations in the park and learned of different species of butterflies and where they can be found.

Being a part of the Virginia Master Naturalist has opened me to new experiences while being around people who share in a similar vision of conservation and a love for the ecosystem.

Bonita Russell loves all plants and volunteering!

Bonita Russell loves all plants and volunteering!

When we put the word out inviting people of color within the VMN program to share their experiences in our newsletter, Ted Munns, President of the Northern Neck Chapter of the Virginia Native Plant Society and a Virginia Master Naturalist volunteer in the Northern Neck Chapter connected us with Bonita Russell. Bonita is an active Master Gardener volunteer and member of the Virginia Native Plant Society who has been making a difference for natural resource conservation and education in the community.

Bonita Russell retired about five years ago, and joined the Northern Neck Chapter of the Virginia Native Plant Society soon after to pursue her love of all plants. More recently, Bonita became a Virginia Cooperative Extension Master Gardener volunteer. A long-time Master Gardener, Diane Kean, contacted her and asked her to consider joining the program. Bonita was reluctant at first, worried that she didn’t have enough experience or knowledge of things like Latin names for plants. But, Diane really encouraged her, and even met her to carpool to the registration session in Kilmarnock. “If it wasn’t for Diane Kean, I would not have become a Master Gardener.” Bonita wants others to know that you don’t have to have a lot of experience. “You don’t have to know a lot. They’ll teach you what you need to know.”

Bonita has put what she has learned through the VNPS and Master Gardener program to work in both her own garden. In 2005, she had moved from Richmond to a 2-acre property on the Northern Neck. Creating gardens was appealing to her, because she didn’t want to have to mow so much! She started with a small section and now has converted a big area of the property into gardens. She especially likes gardening with native plants, “because they take less water and support native insects.”

What she really enjoys about being a Master Gardener, though, is the volunteer time. In her volunteer role, she assisted other Master Gardeners with programs at assisted living and rehabilitation centers in the area and to answer plant questions from the public at the farmers markets in Tappahannock and Montross and at the Master Gardener Help Desk. As part of the VNPS, she led the maintenance of the native plant garden at the Heathsville Courthouse, coordinating and participating in monthly work sessions there. Bonita also helps with upkeep of the historic gardens at Stratford Hall and the George Washington Birthplace. As you can see, she is a very active member of the community, helping to create habitat and educate others!

Bonita says her favorite native plants are golden alexander, butterfly weed, and passionvine. But, she loves them all, and she loves the joy and satisfaction she gets from observing plants. A t-shirt gifted by her daughter says it all: “You’re never too old to play in the dirt.”

Three Volunteers Tell Their Stories Read Post »